(based off of materials created by Stefan Rajkovic)

Here's a diagram that's a good way to think about Git. ![Git Schematic] (https://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/~adanner/cs40/f14/gitrepos.gif)

Notice that commits and adds are done to track changes locally on your computer, and push/pull is for synchronizing what you have on your machine with something that is stored online (i.e. remotely).

This also suggests how Git can be useful if you want to work on the same piece of code with someone else (e.g., have you ever made 10 versions of the same project, each slightly different, and tried to figure out how to put them together? With Git, this will happen much less).

How Git actually works is very cool, but for now just focus on getting used to using it.

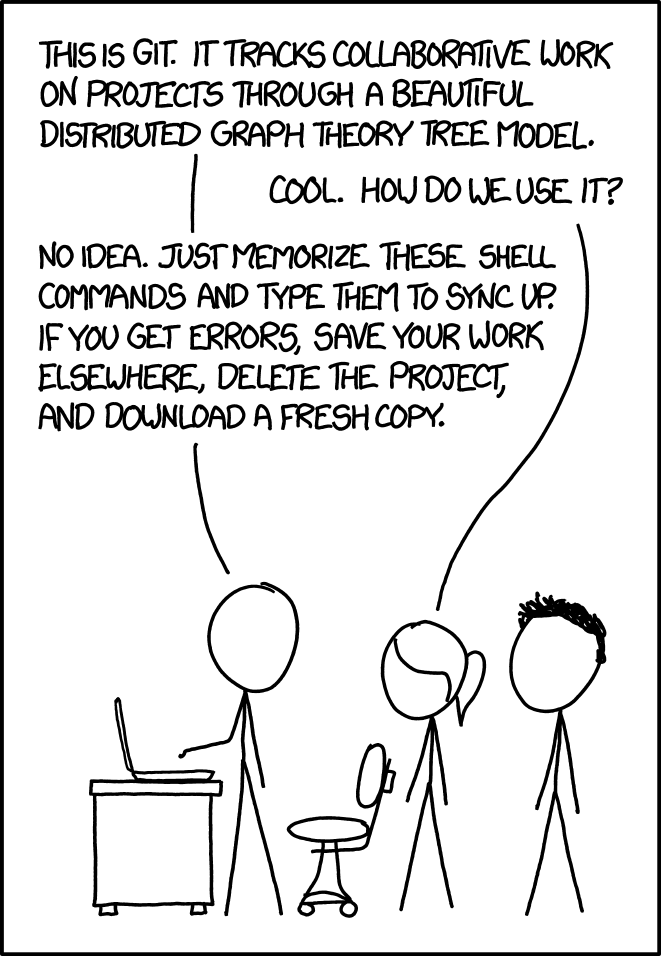

Relevant xkcd:

This repository, like many others, has a limited list of people permitted to commit to it (maintainers). In this case, it's just me. So, to start off, we're going to have to fork it. Click the button on the left side of your screen that says "Fork". Once you follow the directions there, you should have a copy of the repository on your own account.

Git is a distributed version control system, meaning that everyone has their own copy of the repository (go look at the picture at the top again).

You create your own copy by running git clone. Find the clone URL of your copy of the repostitory, in

the same place as you would have found it for ps0, and clone the repository by running

git clone <repo_url> git-tutorial in your terminal. That last argument is the name you want

the folder holding the repo to have, so let's run cd git-tutorial to move into that folder.

Now it's time to do some work. Make some changes to the repository. Start by editing this file (maybe put your name somewhere on this file). Also, add a new file. The easiest way to do that is to run touch new_file.

Now, run git status, and you should see something like this:

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.md

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

new_file

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Let's break that down. After some info about what branch you're on (more on that later), you'll see

Changes not staged for commit:. Staged is git's fancy word for ready to commit. Changes you make

won't be commited unless they're staged first. This let's you only commit some changes, down to line

level granularity (e.g. if you really want you can change multiple lines in a file, and only commit

one of them, without losing any of the work on the others). The second section below is untracked files,

which is files that git isn't paying attention too. Adding changes to the staging area and adding files

to be watched is down the same way, by running git add. To add both of those files, run

git add README.md new_file. You can also run git add --all, or git add ..

The first one adds all files, and add every file and all changes. The last adds every file in the

current directory, recursively.

Some files you don't want tracked (also known as checked in)by git. These could be something like config files for your text editor, or they could be secret keys that you need for configuring your project, but that you certainly don't want to share. As a rule of thumb, a few things you don't want to track in git are:

- config files that are unique to you/your editor

- secrets

- build artifacts

You might be wondering what build artifacts are. It's anything that one can regenerate given the source code,

so any compiled binaries, or anything of that nature. In OCaml this is typically the _build folder, and any files

that end in *.byte, *.cmi, or *.cmo.

Rather than having to be incredibly careful not to add these file each time you commit, it's often easiest to write

a .gitignore, a file that lives in your git repository (and does get checked in), and tells git which directories

or files to ignore. Some git hosting services, like GitHub or BitBucket will let you autocreate .gitignore files

based on the language your project is in, prefilling it with things like the above list for OCaml, or *.o for C.

Short for difference, the diff is the changes you've made. Before you add something to the staging area, you can run

git diff to see your changes. If you've already added but not commited, you can run git diff HEAD, and if you

already committed, then git show will show you the diff from your last commit.

Once you've added something to your staging area, you need to commit it. You can do that just by running git commit,

which will bring up a console text editor to add a commit message. The default is often vim, which most people

don't even know how to exit properly (if you're stuck, you can close the terminal. Otherwise, :q! should get you out). If you want to change it, you can run

git config --global core.editor "<your_favorite_editor>", replacing your favorite editor there. Note, that you'll

likely want a console based editor, like vi, emacs, or nano, in there, since git doesn't exactly play nicely

with GUI based editors in my experience.

To avoid the whole tango of going into an editor, you can just run git commit -m "Commit message", and write your

commit message there instead. I highly recommend this.

To avoid having to add files manually, you can also run git commit -a, which will commit all the changes you've

made. Combine them into git commit -am "message" to commit all your changes easily. Careful: git commit -a

doesn't work like git add --all, it doesn't check in (start tracking) any new files, it only commits changes

to existing files.

Realistically, most of your commits will look like git commit -am "meesage".

Every git repository comes with a default branch master. Branches are seperate lines of commits, that can be

merged into each other. Branches are most commonly used to keep unfinished functionality out of master, so it doesn't

break anything else. Many organizations have the master branch be only the most current stable version, and keep

a develop branch with works in progress that have been tested individually, but aren't ready for release, and many

feature branches, such as stefan/add-gifs, on which developers write new features or fix bugs, test them, and then

merge them into develop. Every so often develop get's merged into master for a release to be made. Obviously,

this is only a general framework and many organizations use different protocols.

To make a new branch, run git checkout -b <branch_name>. From there, you can use git checkout master to get back

to master, and use git checkout <branch_name> to get back to your new branch. Run

git push --set-upstream origin <branch_name> to push your branch to BitBucket.

In your projects in CS 51, you probably won't have to make branches, but it is a good feature to know about. If you ever do any work that involves coding (e.g. TF-ing this course), you'll probably use the branch command quite a bit.

Merging is a method of combining branches. Make any change on your separate branch, commit it, and then switch back

to master. Now imagine you want your change here in master too. Git has an easy way of doing that: run

git merge <branch_name>. This is a pretty simple change, so it should work without a hitch. It'll move that commit

onto your master branch and make a new empty commit that let's people know which commits were merged in.

What if while you had been working on your branch, someone else had made changes to master? And those changes

conflicted with yours? Git will automatically merge anything it can, but if you and a friend both changed the

same lines, git doesn't know what to do. It will tell you theres a merge conflict, and you need to fix it.

You can run git mergetool, and it'll show you both sets of code side by side, and let you choose. You can

also just edit the files that have conflicts (what command would show you them?) in your favorite text editor. This can look very scary when it happens the first time, but don't panic and you should be able to work through any issues.

Once you're done, run git commit and it'll bring you to the editor and let you finish the merge.

If other people are working, and make changes to master, how do you get them? The easiest way is simply to run

git pull while on the branch you want to update. It'll merge the online version into yours. Oftentimes you'll

want to run git pull --rebase instead, so that any commits you've made to master appear after theirs, and so that

you don't get an empty merge commit message just for updating your branch. The rebase flag makes it run a rebase

instead of a merge. Rebasing is a little bit more complicated, and if you're interested in the difference and why

it matters, then we can talk about that after code review. One important note is that you can't pull if you have changes

you haven't commited. But what if you don't want to commit, since you're code is still sort of broken?

You can stash all of your changes using git stash. After that you'll be clear, and you can pull. Run git stash pop

to recreate all of your changes. Git's stash is a stack (as you might have guessed from the pop), and so you can

keep stashing things and pop them off in reverse order.

What if you want to see a history of commits? Run git log, and you should multiple entries like this:

commit c90bf58fab72874519b2837b1033a53cdecb5847

Author: Kevin Lee <[email protected]>

Date: Fri Feb 3 02:27:55 2017 -0500

kevin's edits

The first line is the hash, a unique identifier for every commit, based on the changes in that commit. The second is the author, typically a name and email. The next is the date the commit was created, and finally the commit message. Just a note that anyone can set their name and email to anything, which is why git uses your SSH keys to identify you. It is possible to PGP sign commits, which verifies from whom the commit is coming, but that's complicated, and totally unnecessary for this course.

So, you've been working on your own repo this whole time. What if this was an open source project you wanted

to contribute changes to? You'd have to open something called a pull request. Head back to my copy of the repo,

and click the "Create Pull Request" button above the fork button. A pull request is a request to merge code you've

written into another person repository or branch. For open source, you'll typically follow this system, of forking

the repo and opening cross repo pull requests. Within an organization, like a company, you'll often just create a

branch and then pull request from that branch into master, or wherever is appropriate. You should be seeing a screen

that lets you pick which branch you want to merge from, and which one you want to merge into, as well as a place for

you to write a message, and maybe add some reviewers. If you clickthrough and open it, you should be brought to a page

with the pull request and info about it, such as the diff, and the list of commits.

The commands you'll use most are probably:

git add

git commit

git push

git pull

Once you start working with partners, you might find yourself using branches, or having to deal with merge conflicts.

This is just a brief taste of git, which has an incredible number of other features, like reflog, bisect,

cherry-pick, and blame. You probably won't use many of those, even when working with others on huge projects

in the real world. I've still never used bisect, and only once used reflog, when myself and some partners thought

we had lost a few hours of work during a HackWeek at Square (source: Stefan). On that topic is git's best strength. It's (near) impossible

to lose anything if you're using git right. Even if you're using it wrong, it's still really hard to lose anything. You

really have to try, as long as you follow these rules:

- Commit early

- Commit often

- Push

- ???

- Profit

Hopefully that's all you'll need to know about git for a while! If you have any questions, feel free to ask!

Sidenote: Dropbox has been known to horribly corrupt git repositories, so if you're still in the CS50 habit (the old CS 50 did this) of keeping your code in Dropbox for it's autosync features, I'd recommend you avoid that, and get used to commiting often. It's even possible to clean up your commits so that there aren't so many, so don't feel bad about spamming your git log.